A few months ago, I realized the thing I’d built my identity on—intelligence—might not survive the AI era. It hit harder than I thought it would. If AI keeps getting smarter, cheaper, faster… what exactly still makes me human?

That question sent me into a quiet existential crisis—and down a rabbit hole. I’d always thought intelligence was what made me—me. But if it’s not, then what is? What does make us human?

The answer I landed on is simple: we die, AI doesn’t. Our attention is sequential, AI’s is parallel. The implications are obvious. Our attention is precious—we can give it to each other in a way no AI can replicate. And our mortality is the ultimate accountability mechanism—it lets us carry risk, accept vulnerability, and build trust. Put those together and you get something only humans can do: feel what’s at stake. Risk is what gives meaning to experience.

New question: If attention is our most precious currency, how was I spending mine? Recklessly—judging by my use of media, tobacco and other hits of stimulation. Restlessly—speeding past the truth that life has a deadline.

In an effort to start living more intentionally, I was looking to reset my dopamine levels. So I went to a Vipassana meditation retreat. What it triggered was anything but simple or obvious. The result was chaotic, beautiful, and enlightening. Almost transcendental—almost, because it’s not over yet.

Here, I synthesize what I’ve learned—through the framework of my body—over the past two months. Everything in this article comes from direct experience. I believe most people can experience the same—for most of my claims, I share supporting peer-reviewed scientific articles.

My Vipassana experience crystallized one insight: consciousness hinges on attention to sensation. Let’s start by defining what sensation is, move on to why it’s important to feel sensation and why we don’t/won’t, and finish with how to do it.

What is sensation?

When I say sensation, I’m not referring just to the inputs from our senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste, balance and proprioception (movement & position). These are just a small slice of the full picture. The “picture” is only complete if we include interoception - what we feel inside our bodies. Here’s an incomplete list to give you an idea: pain, pleasure, temperature, pressure, tension and movement that we feel in our organs, muscles, nerves and bones.

Sensation inside the body is data that guides our decisions and actions, most of the time without our realizing it. Everyone feels sensations like hunger, sore muscles, or racing heart. These signals tell us about the state of things inside. But sensation also stands between the outside world and how we think, feel and react.

Say you cut your finger while cooking: first you feel the pressure and friction of the skin against steel. Then you feel the pain of your flesh tearing and the wetness of your blood flowing out of the cut. Now imagine it’s not an accident—it’s an attack. Same knife, but now it’s life or death.

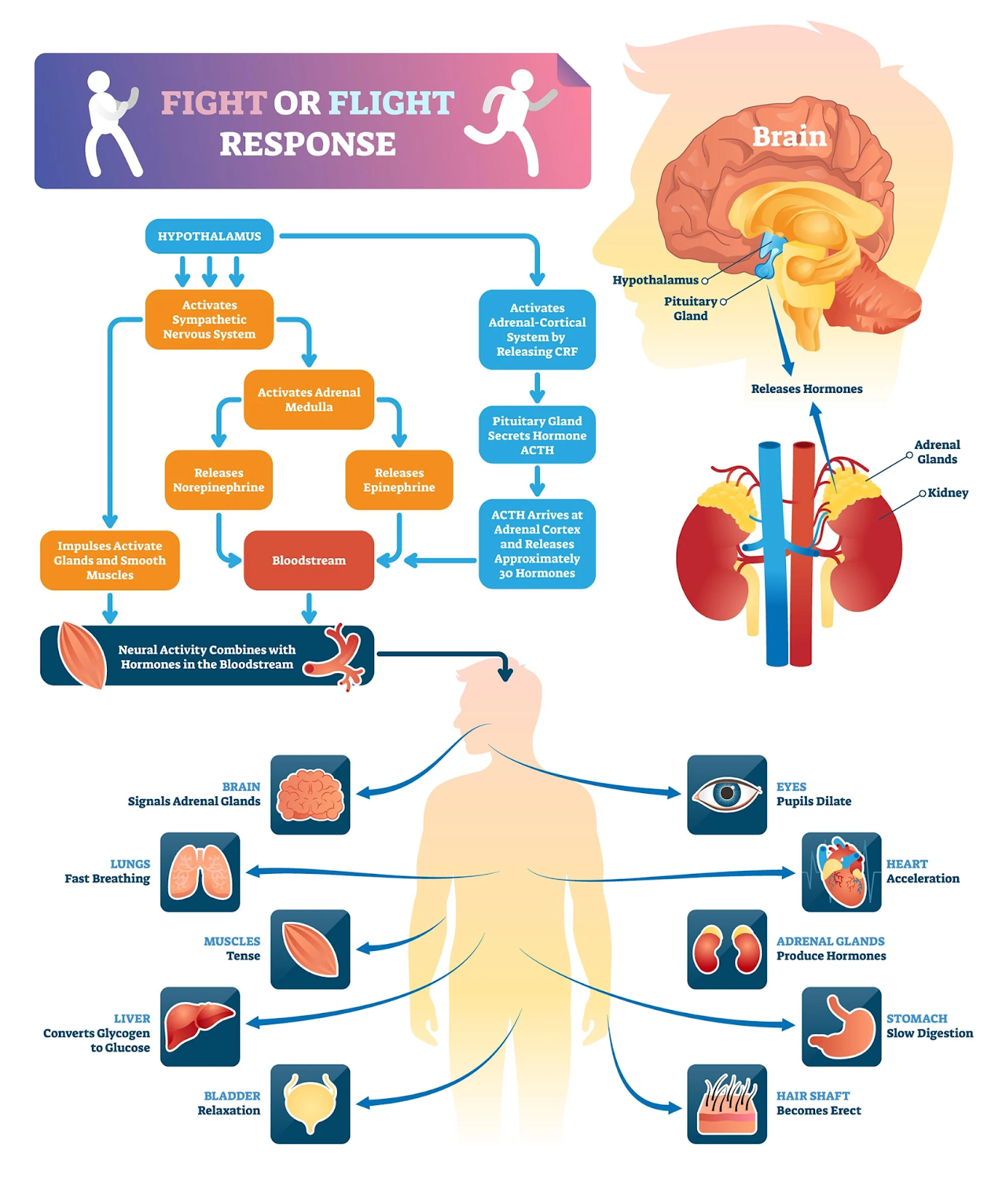

Your nervous system sends a fight, flight or freeze signal to your body: muscles tense up, heart accelerates, hair raises up, and more (image source). The big difference between these two situations is that one is life-threatening, and the other not. Before you even have time to label what you’re feeling or decide what to do, your body interprets what it thinks happened and selects a response depending on the situation.

We tend to believe the rational mind has the final say on what’s real and what to do. But the rational mind is always catching up. Here’s a rough timeline—from external event, to sensation, to thought, to action. There can be overlaps between the different steps, but interoception is the first actionable signal available to consciousness. It’s how firemen do the right thing in a fire, before knowing why.

Sources by stage: 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9

Importantly, the receptors that alert us to fight or flight (and all the others) aren’t “asleep” when nothing dangerous is happening. Never, really. We can (learn to) probe them at will, and we can open ourselves up to perceiving their more subtle signals without probing (e.g. before we make a decision). Let’s stick to probing for now though.

To quantify how much sensation you can feel, try this quick exercise. Take a moment to focus on each of these 10 parts for <30 seconds, one by one: scalp, chin, optic nerve, ear canal, clavicle, thyroid, pancreas, kidneys, skin on the inside of the elbow, inside the ankle joint. What the part in focus should feel like: lighting up (without tensing), distinctly (almost like with borders) from what’s not in focus, every tingle/pain/contact/etc. becoming vivid.

How many of these can you feel? A couple of months ago I could probably barely feel two. Now I can feel all of them after 1-2 seconds of focus. Of course, not all at the same level of intensity, and some parts I didn’t list still remain elusive.

Learning how to do this has multiplied the quality of my life countless times.

Why feel all the sensation?

OK, so what’s the point of all this?

When was the last time you watched a black and white movie? When was the last time you sat through a video/song buffering? We crave fidelity. Once we taste more of it, we rarely want to go back—except maybe to focus.

If you could feel fewer than 5 body parts in the quiz above, you’re probably living in black and white, on mute. In my own experience, it actually takes more energy (literal calories) to block sensation than to feel it. More insidiously, avoiding sensation isn’t surgical. The same circuits that let you feel grief also let you feel awe. Numb one, numb many.

Our instincts, intuition, gut feeling, heart breaking, and so on, are deeply rooted in the physical, palpable reality. Feeling the full extent of sensation enables effective decision making, emotional intelligence, genuine relationships, good health, high mental performance, and much more. There’s more to feel in food, showers, color, sex. There’s hardly any other way to be truly conscious and fully human, without experiencing all sensation.

Sometimes the signal is noisy (e.g. we fawn instead of fight or flight) due to trauma (physical or emotional it’s all stored in the body anyway)—but this can be fixed by feeling sensation. Sure, it could take some getting used to at first (especially in the face of trauma)—I’m not arguing to experience all sensation all the time. Rather: open awareness to all possible sensations—listen better when the body does have something to say.

Let’s take empathy as an example. Empathy is driven by mirror neurons. They help us simulate the emotional states of others. But how can we expect to simulate anything if our simulator is turned off or in power-save mode? Take it further: how much love can we really feel—or give—without empathy? Maybe some at a cognitive level. Probably as much as ChatGPT (tangential but relevant reference). Coke-Zero love, if you will.

Another one—this time from high-stakes finance. Researchers found that traders who could accurately track their own heartbeats outperformed their peers in both profits and survival on the floor.

Now combine that with imagination. You’re contemplating a big, risky life decision. Your future is on the line, you visualize yourself in it. You imagine how you’ll like your life depending on your decision. Your mirror neurons rev up and trigger sensation according to that imagined future you. If you feel that sensation, you run a chance to do your future self a favor rather than toss a coin.

Experiencing the above examples through enhanced sensation was eye-opening, but somehow within expectations. What happened to my body and brain at a physical, palpable level was a surprise. Here are some changes from the past 2 months, since I’ve learned how to focus my attention on my body. The list is growing every day.

- On demand recovery/repair:

- Regained feeling in the tip of my toes, that I’d lost due to crappy shoes; lost most of my torso fat (averaging -0.5kg/week); started regrowing my pattern hair loss

- Released long-held tension—neck, back, hips—that had blended into my baseline

- Doubled my sports recovery speed—I can do twice the # of workouts without feeling more tired or eating more

- Senses (vision, hearing, etc.) heightened——beyond anything I imagined

- Improved physical performance:

- Yoga: after 7 years of practice, I suddenly gained 20–30% more range in twists and stretches; good posture doesn’t take work anymore. It’s automatic

- Bouldering: grown +1 difficulty level (was stuck on it for the past year)

- Running: my marathon time (as calculated by my Garmin watch) has been improving at 2x to 4x my previous best (2-4 min/week vs 1 min/week); my VO2max has grown from 53ml/kg/min to 57ml/kg/min (that’s from top 25% to top 10%)

- Sleep: naturally wake up after 6h30min vs 7h30min, without a drop in energy

- Improved cognitive performance:

- Creativity flows again: brainstorming, writing, improv all feel natural—not forced.

- Full agency, no procrastination: I can get started on tasks immediately, just know what needs to be done, just do it until it’s done (vs. needing to scroll or snack before getting to work & getting lost midway)

- Improved long term memory: I started remembering things whenever I need the information or I ask myself the question

- Improved emotional performance:

- Heightened self-confidence: can’t even begin to describe this, my baseline was quite low

- 4x the emotional awareness, management, reactivity: I can now recognize emotions as they build up and consciously decide what to do (took me 6 years of therapy to get to 20% of my current ability—rough estimate, of course)

- Increased calm and minimal anxiety: SSRIs took my anxiety from 7/10 to a 3/10. Now I’m at 0

- I still smoke, but my relationship with media & technology has changed dramatically. The need to scroll, check notifications, listen to podcasts, etc. essentially dissolved. I’ve virtually stopped drinking

Sounds fantastic, right? Too good to be true. My hypothesis—and here’s some backing: 1 , 2—is these changes are rooted in the connection between the body’s sensing and repair functions, like how maintenance teams use sensors in aircraft to inform repairs. Your mileage may vary, and some of these are subjective, but I tried my best not to embellish.

If AI is the new benchmark, feeling might be the new thinking. I believe most people can experience this. But why do they not?

Why we don’t feel sensation?

If it’s so powerful, why isn’t everyone doing it? One thing or the other prevents us from tapping into sensation. Here are four hurdles from my own experience.

Why fix it if it ain’t broke? If you read this far and still don’t think it’s worth the effort—I get it. Maybe you don’t buy my story. It’s really hard to want something you can’t imagine. I’m selling you a “box of chocolates”, but it doesn’t have a picture on it, and you’ve barely ever had “chocolate”. Staying in situations that make us a known amount of miserable is easier than change that could go either way, because losing stings twice as bad as winning feels good.

As long as we haven’t seen the other side, our mind will estimate that it’s not worth the gamble. More insidiously, sometimes we see glimpses of what life could be. Maybe in therapy. Maybe in love. Maybe (ahem) with psychedelics. We cling to those glimpses. So we freeze—afraid progress might shatter a fragile new equilibrium.

And what if it’s too much? What if life gets worse instead of better? We train ourselves to suppress the sensation we don’t like. We seek sensation we like, sometimes in self-defeating loops. Paradoxically, the “training” is really an atrophy that covers both pleasant and unpleasant sensation. Conversely, overstimulation burns through our interoceptive sensors, like staring at the sun.

How could we not? We’re monkeys riding lizards flying starships. The controls are blinking with signals we were never trained to read. The lizard flinches. The monkey reaches. We borrow from our future dopamine-cortisol balance without knowing the interest rate. The interest compounds: pain accumulates; pleasure depreciates. Eventually, craving and aversion, meant to motivate us and keep us safe, become noise in the cabin: too loud to ignore, too vague to follow. We need to rack up some courage before we take a leap of faith.

It’s too hard and ambiguous: So you want to feel sensation. How do you start? Psychology often points to “emotional intelligence” skills: self-awareness, self-regulation, motivation, empathy and social skills. Observing sensation is suggested for building these skills, but it’s emotional literacy (the ability to identify and name one’s feelings, framed through the six basic emotions) that supposedly plays the fundamental role.

After six frustrated years in therapy trying to learn how to do this, I believe the approach is backwards. Things are getting better: a new wave of therapy modalities incorporates mindfulness, somatic and trauma-informed approaches. But they’re getting better in tiny increments, missing a central piece of the puzzle: attention skills.

It’s too much work: The initial time investment in attention skills, to start experiencing meaningful sensation (see quiz above), is roughly 100 hours. At least 50 of these need to be in a silent retreat (my estimate, could vary). That’s because training attention takes a lot more energy (think calories) than our brain usually has in its “discretionary” budget. A silent retreat temporarily stops many of the “big spenders” (language, our internal narrative, and speaking). This might sound steep, and that’s understandable.

How to feel sensation?

Say you want in. How do you actually build this?

How well we place attention on sensation depends on four factors (my observation, not peer-reviewed): Precision, Stability, Intensity, Range. We can train each of these building blocks separately. Going to a silent retreat (I recommend Vipassana) armed with these makes success much more likely.

Precision

Sensation often arises in small areas of the body (e.g. an eyelash on the cheek). The resolution of attention limits what we can perceive. Feel more detail, and more becomes feelable. To train precision, I recommend training your convergence/divergence skills & other eye exercises, and any sport that needs precise eye-hand coordination.

Stability

Between the moments of focus on a location and perception of sensation, focus needs to be on the same spot continuously. Stability depends on one’s ability to ignore distractions, pleasant or unpleasant. To train stability, I recommend working on both types of distractions:

- Pleasant: using a floating tank, training inhibitory control

- Unpleasant: taking cold showers, using a shakti mat

Intensity

The more subtle the sensation, the more intense the attention needs to be. Like squinting to see farther. Intense focus takes calories, which are often budgeted for other things (talking, moving, thinking, etc.) To train intensity, I recommend going into nature alone and observing something that has a lot of tiny details (a tree, a bird, the night sky) for at least 30 minutes at a time.

Range

Interoception data is disproportionately more useful when it can come both from entire systems (e.g. all the skin, or all the muscles) as well as from specific points (e.g. the fingertip). Coherent interoception—being able to probe any part on demand—requires a critical mass/surface/volume of the body that you can cover with attention (i.e. at some point it clicks together). I don’t know of any drill for this skill, but basic knowledge of anatomy can speed up in-retreat progress by accelerating your body-map building process.

Catalysts

Some experience with psychedelics, can help prepare you for the learning journey—going from very little to a lot of sensation can be strange and overwhelming, until the brain adjusts (2-3 days).

Other embodied practices—like yoga, breathwork, somatic experiencing or dance—can build familiarity with your internal terrain. You’re not starting from scratch if you’ve already learned to listen through movement.

Mindfulness & intentionality for energy management (e.g. minimizing distractions, phone use) helps reinforcement too, not just initial learning. After a retreat, back to the normal world, people often feel like vividness fade rapidly. The vividness can come back too with practice.

Some philosophies and spiritual currents use death awareness (memento mori) as a gateway to feeling sensation—it’s what makes us human, afterall. Imagining and experiencing deadly danger are similar from our brain’s perspective—it can trigger fight/flight/freeze type sensation. However, for this to work well, you need very good imagination, on top of great attention.

Nuance

Finally, my journey is an n=1 privileged tech-bro twist on Buddhist mindfulness. Race, gender, disability, neurodivergence, trauma and many other nuances may call for a different approach. If I sound authoritative, it’s because I believe my experience is real, not because I’m 100% confident it’s effective and safe for everyone.

I die therefore I am. I feel therefore I live

Human sensation seems to be in direct contact with objective reality. And sensation exists only in the context of attention. It’s not just dying that differentiates us from AI. It’s our finite, sequential attention, and our ability to focus it on sensation, other people, the world.

The variety, fluidity and vividness of sensation is a major, if not main factor of the quality, breadth and depth of our experience of life. If the meaning of life is to experience it, then learning to experience sensation is one of the most meaningful investments we can make.

This ability is built into our bodies, but for some reason the batteries were not included. Maybe evolution left them out on purpose. Maybe we yanked them out, jammed them into a sexier toy, and wonder why the remote to our soul won’t click.

But the remote’s already in your hand. The batteries are within reach. And maybe—just maybe—there’s even a manual tucked nearby, if you know where to look.

The show is always on. It’s your choice how clearly you want to see it.

Full color or black and white—what’s it going to be?

This is not the whole story… There is more. Much more.